Obliterated Landscape

26 April - 26 May, 2007

Wednesday-Friday 12-6, Saturday 12-4

Reception for the artists: Wednesday 25 April, 6-8.30 pm

The works in Obliterated Landscape explore the premise that we can never get landscape neat, unmixed, unmediated: its presentation and perception are always contingent on a range of concerns: ideological, ethnic, artistic, commercial.

To produce the series A Month in the Country, Cornford & Cross contracted with photo agency Corbis to hire, for a month, four images yielded by the search term ‘East Anglia Landscape’. These conventional views of the English countryside were printed, framed, and shown originally on home territory, at the Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery. At the expiry of the hire-period, the artists whitewashed over the glazed images, removing them as per the contract from public display but preserving them as objects. As an act of brusque purification the whitewashing has contemporary and historical resonances: for example, of the whiting of shop windows before refurbishment (often enough, following bankruptcy), and of the obliteration of Church murals during the Reformation. It also brought the works into the world of contemporary art: they are now at home in the bright minimalist spaces of the gallery or museum. That this, potentially, may not be the end of the story is hinted at by the title of the series, derived from a novel by J L Carr in which a young man, traumatised in World War I, spends a summer in a country church, laboriously uncovering a mediaeval image of damnation.

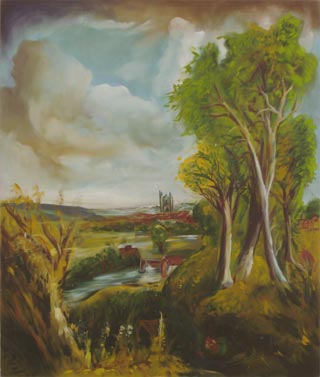

The works in Shezad Dawood’s series Arcadia were commissioned in Pakistan from professional painters of cinema advertisements. These artist-craftsmen were required to make accurate versions of paintings by John Constable from illustrations in books. In one sense Arcadia is a game played with Walter Benjamin’s notion of a work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction: reproductions are transmuted back into artworks of a traditional type: unique, hand-made, in oil on canvas. But the series is above all a metaphor for the clash of cultures, or perhaps more accurately (if we consider that mass-migration is above all a working person's phenomenon), the collision of vernaculars that is taking place across the planet today. The transformation staged by Dawood of, say, Constable’s Haywain into a milieu half-resembling a sub-tropical landscape might be compared and contrasted to the creeping ‘westernisation’ of culture on the Indian sub-continent as reflected in, say, Bollywood film posters.

Saron Hughes’s One Man’s Lawn resembles an oversized envelope fashioned from cardboard, paper, brown packaging tape and a couple of shades of green emulsion paint. It’s almost a discarded colour-field painting. Considered as sculpture it is an extreme self-effacement: it lies flat on the floor at a height of 2 or 3 cm and almost whispers “walk on me". It also suggests much grander perspectives: the dreamy stripey machine-manicured expanses of cricket pitches, tennis courts and country-house greensward, resorts of the privileged. In fact the work was prompted by a dream, a class-based nightmare perhaps, echoing A A Milne's Lines and Squares, in which Hughes was allowed to walk only on the light green stripes. Yet this is “one man’s” lawn: a little excerpted piece of paradise, a lash-up as the architects say, in the same brazen spirit as a DIY neo-classical portico. It intimates its own dissolution in its tacky construction; and maybe that, too, of its putative owner, demarcating as it does a plot roughly the size and shape of a human being.

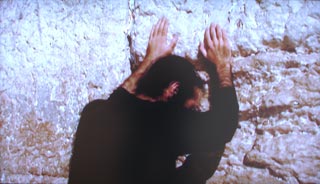

In Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen’s film Mystic Truths (the title refers to Bruce Nauman’s sarcastically-named 1967 neon work, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths) we experience that most fraught and fought-over of locations, Jerusalem. The film is the outcome of a two-month residency in November and December 2006. Larsen’s aim was to present an image of a place and its people which, while acknowledging the archetypes of conflict, suffering and despair that shape conventional reporting, looked beyond them. Hand-held reportage combines with static-camera images of compelling contemplative beauty. Larsen has an ear for the paradoxical statement (a Palestinian woman opines “I like Rambo because he has encouraged me to fight the enemy”) and an eye for the startling playlet (the traffic cop who out-jives even his female counterparts in Pyongyang), but we are moved above all by the sheer visual and intellectual density of these images: a busy palimpsest of nature, man, the traces of history and the generally trashy trappings of contemporary life.

Cornford & Cross, A Month In The Country I, 2003-4.

Rights-managed stock photography, 75 x 100 cm, glazed and framed, whitewashed

Cornford & Cross, A Month In The Country II, 2003-4.

Rights-managed stock photography, 75 x 100 cm, glazed and framed, whitewashed

Cornford & Cross, A Month In The Country III, 2003-4.

Rights-managed stock photography, 75 x 100 cm, glazed and framed, whitewashed

Cornford & Cross, A Month In The Country IV, 2003-4.

Rights-managed stock photography, 75 x 100 cm, glazed and framed, whitewashed

Shezad Dawood, from the series Arcadia, 2004.

Oil on canvas, 102 x 125 cm

Shezad Dawood, from the series Arcadia, 2004.

Oil on canvas, 145 x 122 cm

Shezad Dawood, from the series Arcadia, 2004.

Oil on canvas, 97 x 72 cm

Saron Hughes, One Man's Lawn, 2007.

Paper, cardboard, packaging tape, emulsion, 175 x 93 cm

Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen, still from Mystic Truths, 2006-7.

DVD movie, 00:30:40

Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen, still from Mystic Truths, 2006-7.

DVD movie, 00:30:40